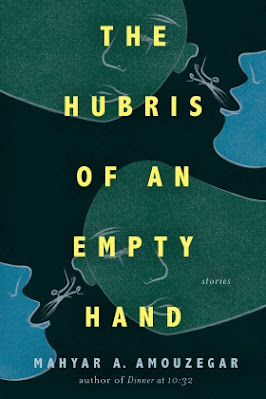

by Mahyar A. Amouzegar

November 18, 2021

9781608012213, 1608012212

Fiction / Short Stories (single author)

280 pages

In eight ethereal stories, The Hubris of an Empty Hand encompasses the frailty and complexity of being human. When some divine gifts fall into decidedly earthly hands, the results are almost beyond reckoning for humans and gods both. Through its wide cast of characters and fascinating settings, terrestrial, divine, or somewhere in-between, Mayhar A. Amouzegar's fourth book of fiction takes on timeless questions of love and its permanence, sacrifice, and the human desire to be remembered and known.

THIS LIFE from the Hubris of an Empty Hand

“Go ahead and ring the bell,” the woman says. She somewhat re- minds me of the nurse from my multitude of visits to the Cancer Center. She is not a tall woman, her head barely reaching the counter that separates us. A small hairpin pulls her short dark hair even further back from her face. She smiles, her eyes focused, and says again, looking at the silver bell, “Go ahead.”

The bell is small but looks heavy, shining under the white light of the hallway. It’s secured within a polished wooden structure, dangling like a hanged man. The hammer, within it, is round, holding a thick white rope.

“Pull the rope hard but only once,” she advises. “Would it matter?” I ask.

“Matter?” She looks at me, tugging on her uniform. It looks like one of those colorful patterned garbs that medical staff like to wear now—out with the simple white and in with the statement. She tugs at her uniform again, more like a habit than the need to straighten the already fitted garb.

“Yes, would it make any difference?” I ask, hoping my insistence will result in the answer I want (I need). I’m looking at the bell and not her, but as I turn to face her, she lowers her gaze.

“I hope so,” she replies. Her voice sounds thin and it fades out. “I mean, would I be better afterward?”

“I cannot answer for you. You have to pull the rope and find out.”

“But what am I doing?” I touch the rope and feel its heavy, coarse texture. I pull back immediately, afraid of disturbing it.

“You’re getting ready for the next stage,” she offers and then displays a quick smile behind her words.

“But what’s the next stage?”

She shrugs. It feels late, and I am becoming impatient. “Where are we?” I ask, looking around this vast unfamiliar space even though I feel it should be known to me. There is no one around, and our voices echo as if the reverberation is needed to solidify our presence.

I feel strongly that we have spent many weeks together. But per- haps it was not her but another nurse who was part of the crew that I saw every Monday through Friday and two Saturdays of the month. It doesn’t matter because, at this moment, she is like my nurse. I feel I know her even if she doesn’t know me.

Another woman appears and stands next to my nurse. She must be my doctor then. I look around to see if there will be others, but it’s only the three of us now. My doctor is holding a large manila envelope. She is wearing a white blouse, and I notice a small tear in the seam. It’s very tiny, so she must not have seen it when she dressed earlier. She was about to hand the envelope to me, but a slight shake of the head from the nurse changes her mind. She puts the envelope down on the counter, takes out a pen from her pants pocket, and prints my name on it. She has elegant hand- writing. The words, large and bold, stare back at me, waiting. “Where are we?” I ask again, hoping the doctor will tell me; perhaps the answer is hidden within the envelope. I want to reach and grab the packet, but I cannot muster the courage.

“You are where you’re supposed to be,” she replies and then quickly adds, “It’s time.” The doctor looks at the bell and then puts her right hand flat on top of the envelope to emphasize the point. Then she adds, “You did well.”

“Did I?”

“Yes. You did well.”

“There was the incident,” I say, too embarrassed to look at her. “True,” she replies in a matter of fact tone, “but believe me, it happens.”

Maybe so, but it’s easier for her to say than for me to bear. It’s not easy to revert to a helpless child within minutes. It is the quick transition from me to a haplessness, and back to myself again, that’s jarring. What is me now, anyway?

I don’t know. I am in a constant state of confusion. Sometimes I have dreams that I am invincible, hold powers that bring solace to others. I do recall my old self, even if it’s hazy and fleeting—perhaps the real me. But those memories are as ethereal as this place. It may be the madness that has afflicted so many people now, has infected me too. Everyday realities are being debated as if truth, like other perishables, can decay. There are signs if one looks for them but fewer and fewer people do. This realization alone brings shudders to my spine.

“Was I powerful before?” I ask.

They laugh, and the sound ricochets and slaps me on my face. They stop when they see the disappointment in my eyes.

“We’re sorry. We laughed because you ask this every time,” the nurse says, though I am sure my real nurse would not have laughed at me no matter my question.

“Every time? I’ve asked this before?”

“Yes,” the doctor says. “We do not have an answer for you. You must move on.”

So, I ask the question that I must have asked several other times as well: “What’s next?”

They have no answer. They don’t know.

“You did well,” the doctor offers again. “Better than we thought. You’ll have to take it one step at a time. We’ve discussed this be- fore.” A doctor’s standard answer, so perhaps she is a real doctor even if the nurse is not my real nurse.

“Yes, but never to my satisfaction.”

She shakes her head. “You’ll never be satisfied,” she says, and then offers the same quick, mirthless smile as the nurses, as if it is part of their training.She is right, of course. She nods and pushes the envelope to the nurse, who instinctively puts her hand on top of it as the doctor had done. The message is clear.

“I will see you soon,” the doctor says and then nods several times before leaving.

“It’s time,” the nurse says. “Will it toll for me or others?”

“It tolls for thee,” she says and with no trace of irony. “I still have a story to tell,” I insist.

“Tell your story once you pull the rope,” she instructs as she walks away, leaving the manila envelope and its content unguard- ed.

I want to reach out and look into the secrets it holds. But I don’t, fearing what I might find. Not all secrets are pleasant. The hall- ways are getting darker, and I know what I must do next.

So I reach over and grab hold of the thick rope.

“Go ahead and ring the bell,” the woman says. She somewhat re- minds me of the nurse from my multitude of visits to the Cancer Center. She is not a tall woman, her head barely reaching the counter that separates us. A small hairpin pulls her short dark hair even further back from her face. She smiles, her eyes focused, and says again, looking at the silver bell, “Go ahead.”

The bell is small but looks heavy, shining under the white light of the hallway. It’s secured within a polished wooden structure, dangling like a hanged man. The hammer, within it, is round, holding a thick white rope.

“Pull the rope hard but only once,” she advises. “Would it matter?” I ask.

“Matter?” She looks at me, tugging on her uniform. It looks like one of those colorful patterned garbs that medical staff like to wear now—out with the simple white and in with the statement. She tugs at her uniform again, more like a habit than the need to straighten the already fitted garb.

“Yes, would it make any difference?” I ask, hoping my insistence will result in the answer I want (I need). I’m looking at the bell and not her, but as I turn to face her, she lowers her gaze.

“I hope so,” she replies. Her voice sounds thin and it fades out. “I mean, would I be better afterward?”

“I cannot answer for you. You have to pull the rope and find out.”

“But what am I doing?” I touch the rope and feel its heavy, coarse texture. I pull back immediately, afraid of disturbing it.

“You’re getting ready for the next stage,” she offers and then displays a quick smile behind her words.

“But what’s the next stage?”

She shrugs. It feels late, and I am becoming impatient. “Where are we?” I ask, looking around this vast unfamiliar space even though I feel it should be known to me. There is no one around, and our voices echo as if the reverberation is needed to solidify our presence.

I feel strongly that we have spent many weeks together. But per- haps it was not her but another nurse who was part of the crew that I saw every Monday through Friday and two Saturdays of the month. It doesn’t matter because, at this moment, she is like my nurse. I feel I know her even if she doesn’t know me.

Another woman appears and stands next to my nurse. She must be my doctor then. I look around to see if there will be others, but it’s only the three of us now. My doctor is holding a large manila envelope. She is wearing a white blouse, and I notice a small tear in the seam. It’s very tiny, so she must not have seen it when she dressed earlier. She was about to hand the envelope to me, but a slight shake of the head from the nurse changes her mind. She puts the envelope down on the counter, takes out a pen from her pants pocket, and prints my name on it. She has elegant hand- writing. The words, large and bold, stare back at me, waiting. “Where are we?” I ask again, hoping the doctor will tell me; perhaps the answer is hidden within the envelope. I want to reach and grab the packet, but I cannot muster the courage.

“You are where you’re supposed to be,” she replies and then quickly adds, “It’s time.” The doctor looks at the bell and then puts her right hand flat on top of the envelope to emphasize the point. Then she adds, “You did well.”

“Did I?”

“Yes. You did well.”

“There was the incident,” I say, too embarrassed to look at her. “True,” she replies in a matter of fact tone, “but believe me, it happens.”

Maybe so, but it’s easier for her to say than for me to bear. It’s not easy to revert to a helpless child within minutes. It is the quick transition from me to a haplessness, and back to myself again, that’s jarring. What is me now, anyway?

I don’t know. I am in a constant state of confusion. Sometimes I have dreams that I am invincible, hold powers that bring solace to others. I do recall my old self, even if it’s hazy and fleeting—perhaps the real me. But those memories are as ethereal as this place. It may be the madness that has afflicted so many people now, has infected me too. Everyday realities are being debated as if truth, like other perishables, can decay. There are signs if one looks for them but fewer and fewer people do. This realization alone brings shudders to my spine.

“Was I powerful before?” I ask.

They laugh, and the sound ricochets and slaps me on my face. They stop when they see the disappointment in my eyes.

“We’re sorry. We laughed because you ask this every time,” the nurse says, though I am sure my real nurse would not have laughed at me no matter my question.

“Every time? I’ve asked this before?”

“Yes,” the doctor says. “We do not have an answer for you. You must move on.”

So, I ask the question that I must have asked several other times as well: “What’s next?”

They have no answer. They don’t know.

“You did well,” the doctor offers again. “Better than we thought. You’ll have to take it one step at a time. We’ve discussed this be- fore.” A doctor’s standard answer, so perhaps she is a real doctor even if the nurse is not my real nurse.

“Yes, but never to my satisfaction.”

She shakes her head. “You’ll never be satisfied,” she says, and then offers the same quick, mirthless smile as the nurses, as if it is part of their training.She is right, of course. She nods and pushes the envelope to the nurse, who instinctively puts her hand on top of it as the doctor had done. The message is clear.

“I will see you soon,” the doctor says and then nods several times before leaving.

“It’s time,” the nurse says. “Will it toll for me or others?”

“It tolls for thee,” she says and with no trace of irony. “I still have a story to tell,” I insist.

“Tell your story once you pull the rope,” she instructs as she walks away, leaving the manila envelope and its content unguard- ed.

I want to reach out and look into the secrets it holds. But I don’t, fearing what I might find. Not all secrets are pleasant. The hall- ways are getting darker, and I know what I must do next.

So I reach over and grab hold of the thick rope.

About the Author:

website-FB-Instagram

The son of a bookkeeper, Mahyar A. Amouzegar, grew up in his home country of Iran surrounded by literature. Every night his father returned from his job at the publishing house with a new title in hand, filling Amouzegar’s childhood home with a panoply of books. Then at age fourteen, Amouzegar left Tehran to live with his older sisters in California. The year was 1978. Delayed by the political unrest that would soon lead to the Iranian Revolution, his parents were unable to follow him to the United States for over five years. On entering adulthood, he found himself balancing a promising career as a national security analyst with his boyhood love of literature. Mahyar is the author of three previous novels, A Dark Sunny Afternoon, Pisgah Road and Dinner at 10:32. His short story, “Tell Me More,” appeared in an anthology as part of The Reading Corner series. Mahyar has lived and worked on four continents and currently resides in New Orleans with his wife and two daughters

No comments:

Post a Comment