Excerpt: Chapter One

I

have watched hundreds of humans suffer through their transformation

from human to Old One. Some say I am an expert in this, but I would

dispute that. I don’t think there are any experts. Too little is known

about the transformation process for anyone to claim the status. The

experience I have lets me ease my patients’ agony a little, and avoids

harming them in the process. But no skill of mine changes the course of

the transformation by a single micron.

I watched Henry Magorian

writhe and twist on the bed I stood beside, reviewing my uselessness,

and finding it ironic that I was so helpless. Henry was Benjamin

Magorian’s older brother, and a slimey wretch of a man. Yet he was my

patient. I was required to give him the best care possible. His family

had flown us out to Montreal from Toledo, Spain, on a private and very

expensive jet, for this purpose.

Pain is pain. I hated seeing

the man claw at the expensive sheets, the tendons in his neck and wrists

standing out like ships’ hawsers. He wore only boxer briefs and his

entire body was bathed in sweat. He had been sweating for hours, now.

We had changed the sheets twice.

I made myself look away. Watching

him helped no one. I put the stethascope on the tray table the family

had thoughtfully provided and looked at Jaimie.

She held her

hands out over Henry’s body, just above the thrashing shoulders,

concentrating on whatever information travelled through her palms. I

wasn’t certain what she could detect, for the mystery of fae magic was

not readily shared by any of them.

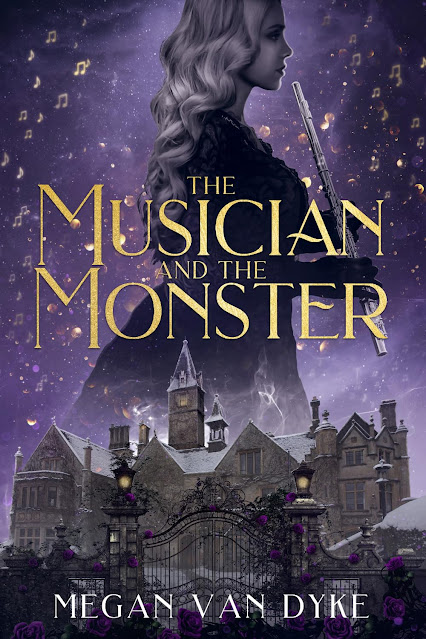

Jaimie wore her thick pale

hair up in a pony tail at the back of her head, which allowed her

pointed ears to be seen. Normally, she was careful to drape her hair

over her ears when among humans, but we’d long since passed that

consideration. We’d been in this room for nearly thirty hours, and

members of the family had stopped stepping in to check on their

cousin/uncle.

She held her flawless face in a stiff, neutral

expression. She was not allowing herself to show how worried she was.

But I’d had seen too many transitions. I was worried myself.

“He’s fighting it,” I said.

Jaimie looked up, then back down at her patient. “Yes.”

It

was the first time either of us had said it, although I think we’d both

guessed as soon as we’d walked into the elegant pale blue and cream

room. The family had bundled all three of us, including Ben, onto a jet

on standby at Toledo’s small private landing field, the moment Henry

Magorian had shown the first signs of transition. It had taken nine

hours to reach Montreal, plus an hour at either end for local travel and

ten minutes of lightning-speed packing.

So we had first seen

Henry over eleven hours after he had begun transitioning, and we’d been

here, save for small cat naps in the bedroom next door, for thirty

hours.

Forty hours, more or less, and he still showed no physical changes.

Henry kicked and moaned, then curled up into a tight ball.

“I

can take away the pain. A little, at least,” Jaimie said. Her voice

was strained. She had slept less than I. Fae could reduce pain by

breathing in bad humours—which was not a medieval conceit for them. It

wasn’t as effective as an angel breathing on the patient, but it did

work.

“You know the danger in that.” We’d both learned that

reducing the pain too much let the patient relax. The transition

required that they move, so that the metabolism was elevated, allowing

the organs to evolve. The extreme fever was another function of the

transition. It was the mechanism that changed the patient’s DNA

expression, the key to the transition. Lowering the body temperature

could suspend the transition, too.

Jaimie put her fingers to

her temples. She had no medical training in her human history. She had

been a soldier in the British army. It was only her transition to a fae

that made health work feasible. She was less used to watching a

patient suffer than I, although she would always find it stressful, no

matter how used to it she became. We all did, despite a hardening of

one’s empathy once exposed to too much of it.

“He should have changed by now.” Her voice wavered. “I don’t know of anyone taking this long.”

“I

have seen some cases last this long,” I said grimly. I didn’t add the

remainder of that statement—that everyone who had fought their

transition for this long did not survive. Jaimie didn’t need that

additional worry. It was quite likely she was well aware of this

statistic. I just didn’t want to bring it to the forefront of her

thoughts.

“Is there anything else we can do?” Her wonderful

silvery eyes were red-rimmed, but still worth staring into. Even after

thirty hours of hard work and worry, even wearing the travel creased

clothing she’d arrived in and slept in, she looked wonderful.

I

pushed away the betraying thought and tried to find an answer to her

question, for the fear in her voice was real. It wasn’t fear of death.

She had been a soldier and now was a fae who dispensed magical healing.

She was accustomed to death.

I knew the source of her fear.

This was Henry Magorian. Ben’s brother. Jaimie did not want to let Ben

down. She wanted to save Henry for him.

So did I, even though I had learned to loathe Henry not long after meeting him.

I’d

sent Ben out of the room hours ago. His pacing and his unhelpful

suggestions, along with his anxious questions every time Henry moaned or

moved, had not helped either Jaimie or I concentrate. As far as I

knew, Ben was in the next room and, as it was two in the morning, Toledo

time, he was probably sleeping, even though bright summer sunlight

streamed through the windows.

It was eight in the evening,

Quebec time, on a blazingly hot day, but none of the external weather

reached us, for this house had a controlled environment kept at a

pleasant twenty-three degrees with just the right degree of humidity.

The window of the room we were in had remained closed and sealed against

the heat outside. The view from the window was magnificent, for the

house stood high upon the exlsuive Summit area, with a jaw-dropping view

of the Old City and the St. Lawrence river twinkling on the horizon.

The

Magorian family could afford the luxury of whole-house environmental

controls, just as they could afford private transatlantic flights, and

bribes to ease an Old One through two nations’ customs and immigration

border checks.

Ben had insisted that they make the arrangements

to bring Jaimie into the country. He had argued that Jaimie could help

Henry as much as I could. The family, desparate as they were, had

complied, although I had no idea what it had taken to make it happen.

Canada was particular about who they let into their country, especially

when it came to the Old Ones. Unlike Spain, Canada had so far refused

refugees, although there were many unofficial refugees flooding across

the Canada/United Stated border. Canada was not xenophobic, though. It

was the first country in the world to acknowledge the Old Ones legally.

Here, Old Ones were not automatically considered “dead” after

turning. They were in a legal limbo, still, but the assets they’d held

as a human, and might acquire as an Old One, were also held in legal

stasis, rather than passed onto heirs. It was a half-step toward giving

Old Ones full citizenship, or at least residency, and the rights and

obligations that came with it. The government was still arguing the

point in Ottawa.

But Jaimie, despite a lack of indentity

documentation, had merely received a nod of acknowledgement from the

customs official who had stamped Ben’s and my passports. I had spotted a

photograph of Jaimie attached to his clipboard.

She stared at me now, hope showing in her eyes, as I appeared to be thinking of another way to save Henry Magorian.

I

desparately wanted to come up with a solution. I wanted her to look at

me with relief and gratitude. I wanted her to….well, that was never

going to happen. But still, I wanted to please her.

So I made myself consider every single possibility. What had we not done for this horrible man? What else could we try?

I

stared down at his curled up body. If he continued to fight the

transition, it would not end well. Did he know that? Did he resent the

idea of becoming an Old One so passionately, that he was putting up

this marathon resistance?

That gave me an idea. I looked at Jaimie. “It’s a long shot.”

“I don’t care.”

That was exactly what I had expected her to say. “That thing Ben did, in New York, with the proto-wizard?”

“The

mind meld?” She didn’t smile at the pop culture name we’d adopted for

whatever it was that Ben had done to the man, as she usually did. She

was a huge Star Trek fan, which I found, well, illlogical, given her

former profession. Or perhaps that was exactly why she liked the show

so much. A professional soldier would appreciate a peaceful utopia.

“What of it?” she added.

“If he could reach Henry, he could tell him to stop fighting the transition.”

Jaimie looked down at Henry, who certainly couldn’t hear us now. “Do you think he doesn’t already know that?”

“He

quite likely does know that. But Henry likes to get his own way.”

He’d fooled Ben into signing over his portion of the family inheritence

because he didn’t like Ben’s choice of lifestyle. “If Ben could appeal

to him, let him see…” I made myself say it. “Let him see that if he

doesn’t let this happen, he’ll die. Henry’s sense of self-preservation

might kick in.”

Jaimie pressed her lips together. She hadn’t

met Henry, but I’m sure Ben had shared with her the reason why he had to

rely on his income as a wizard, when his family was so well off.

“I’ll go and get him,” she said. “A long shot is better than the nothing we’ve got without it.”